Top Three Parenteral Therapy Packaging Failures

Pharmaceutical products fall into two categories, non-parenteral/enteral and parenteral. For the layperson’s understanding, non-parenteral is any substance that is administered via oral, topical, intestinal (i.e., feeding tube), or suppository. Parenteral then refers to bypassing the digestive tract in favor of injection or intravenous delivery.

The ongoing rise in demand for parenteral innovation in formulas and mechanisms is born of the quest for faster and longer-lasting results, maximum bioavailability attainment, and preferences for single-use products. The primary packaging of parenterally delivered medicines and their accoutrements must contain and protect the sum of their parts to the point of use in the human patient. Primary (and secondary, but our focus here is primary) packaging for parenteral drugs is at the frontline of ensuring those protections. The high-tech and sophisticated nature of new medicines arrives with many fragile proteins, suspensions, and lyophilized ingredients.

What Can Go Wrong

Labeling Errors. This packaging failure seems so avoidable on its face yet is a persistent source of industry challenge. While labeling errors are not limited to parenteral drug labels, the nature of parenteral delivery presents potentially more dangerous consequences. Even with the addition of bar codes, confusion and errors persist. A major culprit appears to be in large volume parenterals—IV solutions and medications. The FDA and European regulators continue to discuss solutions, but with FDA draft guidance published in 2013 remaining non-binding, an optimal solution remains elusive. Efforts to reduce extraneous label content, improve bar code quality and prohibiting foil/opaque light-protective overwraps have all been considered, yet in the US and abroad, consensus and application remain low.

Most parenteral error reports are related to the universally recognized soft plastic IV bags. A cursory look at the prolific roster of products in that format is all it takes to understand the propensity for confusion. Look-alike bags, similar labeling and drug names, bags offering different dosages of the same medication, etc. make it clear why industry is rife for mix-ups. A good example of similar drug names (in lookalike bags) is Dobutamine and Dopamine. Another common error occurs when labels present different dosages and strengths that appear in identical fonts, color, and size on bag labels, i.e., 1,000 units/500 mL vs 25,000 units /500 ml. And yet another reported vulnerability is premixed bags of the same medication that come in a variety of base solutions – AND multiple strengths. This nagging issue is one every industry professional and human factors panel should keep in mind as an opportunity center.

Particulate Contamination. Glass vials and ampoules are commonly used in parenteral drug packaging. Glass (borosilicate type) is nearly impervious to water degradation. It withstands temperature variations, is sterilization-friendly and is non-reactive to most chemicals, extending shelf-life and potency. The risk of glass, however, is particulate contamination. Particulate entering the vial contents can happen during manufacturing processes such as washing prior to filling, improper handling at any point throughout production, or delamination, most likely to occur due to post-distribution conditions or factors (delamination is more likely to occur through aging). The natural transparency of glass (even colored glass for protection from exposure to light) allows fast, easy visual inspection for any anomalies, such as change in color or clarity of contents, level of fullness.

Ampoules remain popular for small volume injectables internationally, while ampoule use in the U.S. continues to decline. Glass-sealed ampoules have a high risk for glass particulate contamination since the ampoule is broken to access the contents.

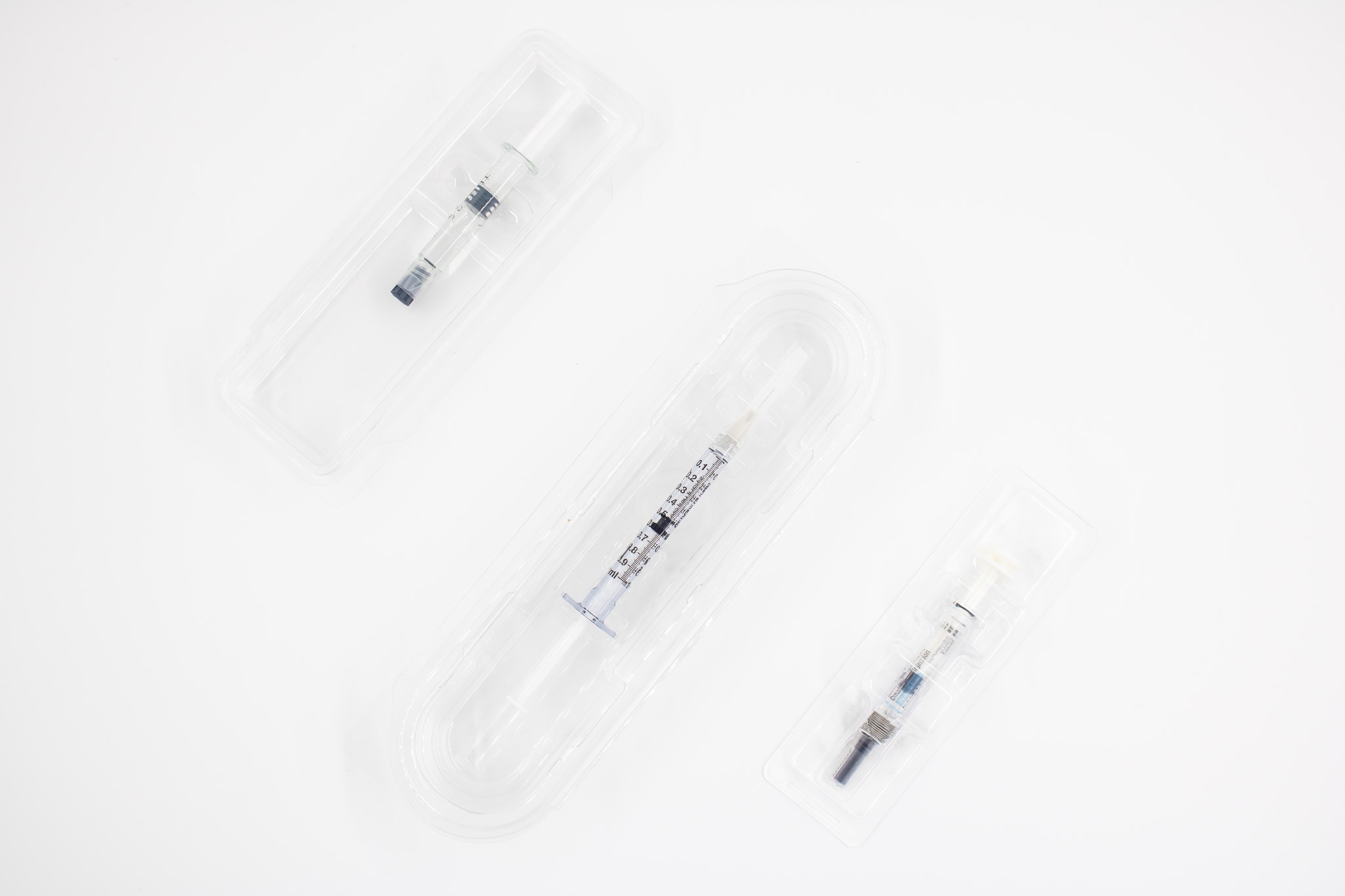

Container Closure Integrity. Parenteral drug delivery presents the highest packaging risk for container closure integrity. When packaged as vials, cartridges, auto-injectors or prefilled syringes, a well-planned container closure system is imperative to minimize contamination risk. Particularly with the rapid growth in biologics, primary packaging systems for parenteral drugs holds new significance. A breach of just one micron whether in the stopper, under an improperly crimped aluminum seal or a faulty flip-off protective button can drastically increase the risk of bacterial contamination. Of note in closure design is rigorous scrutiny of elastomeric composition. Variations in hardness, viscoelasticity and modulus are considerable. Depending on the properties of the drug formulation, life cycle and clinical use, confirming the best choice for the container closure system should be a priority.

As with every facet of medical innovation, the list of possible failures goes on. Fortunately, in the same way, so does the full potential of what is to come.